Hong Kong’s dense urban landscape faces a growing challenge that extends far beyond mere discomfort: extreme heat is becoming a critical public health concern. As the city’s population ages and urbanization intensifies, the risks associated with rising temperatures are becoming increasingly complex and dangerous.

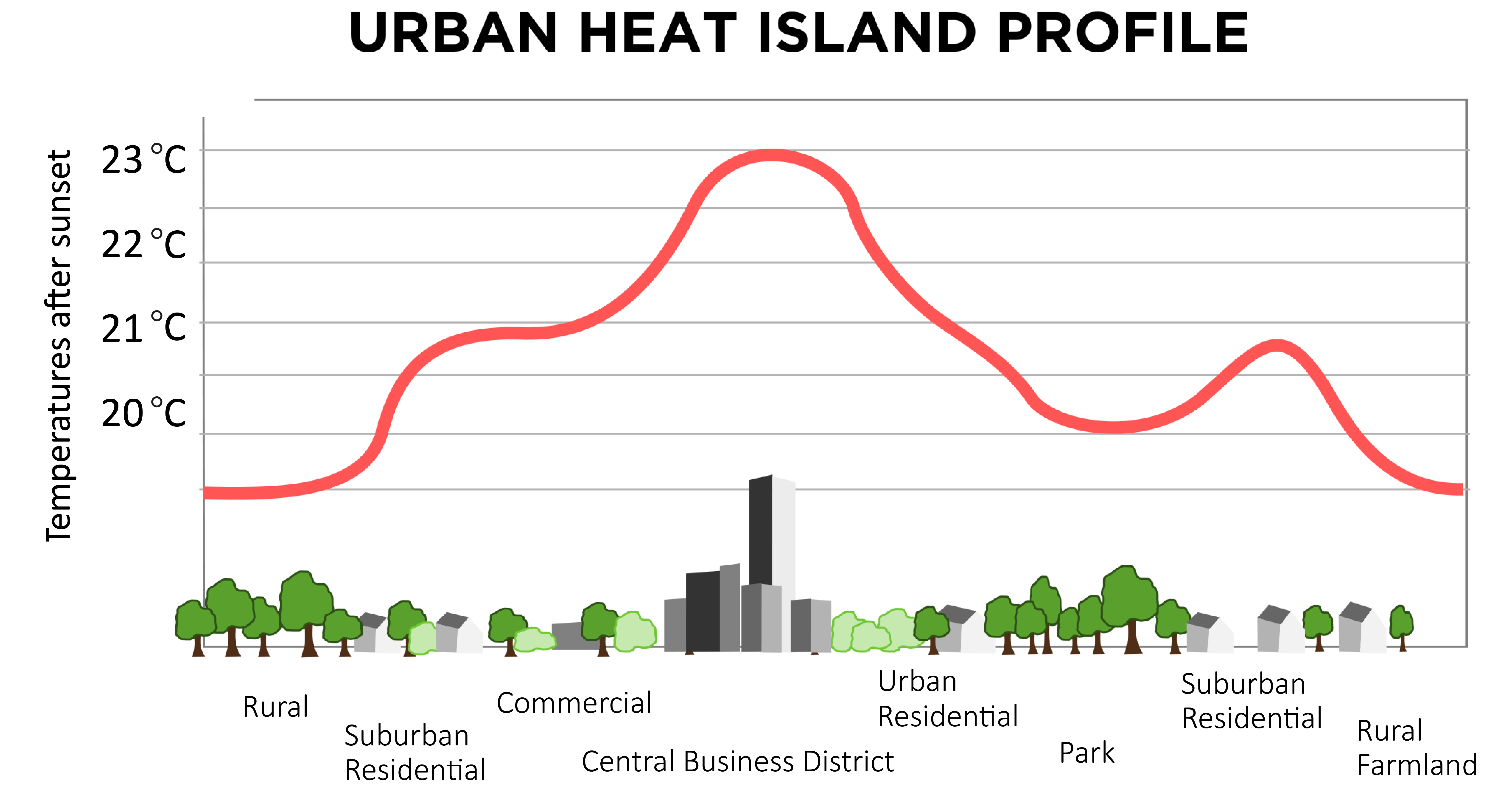

By 2033, nearly 27% of Hong Kong’s population will be over 65 years old, a demographic particularly vulnerable to heat-related health impacts. The urban heat island effect compounds this risk, transforming city spaces into heat-trapping environments that can be significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas. Sub-divided living spaces, often lacking proper ventilation and cooling, further exacerbate the problem for many residents.

Recognizing these challenges, Hong Kong has developed a multifaceted approach to heat management that combines scientific research, technological innovation, and community engagement. The Hong Kong Observatory (HKO), established in 1883, plays a pivotal role in this strategy. By collaborating with institutions like the Chinese University of Hong Kong, they’ve developed the Hong Kong Heat Index—a sophisticated two-tier system that provides nuanced heat stress information tailored to the city’s hot and humid climate.

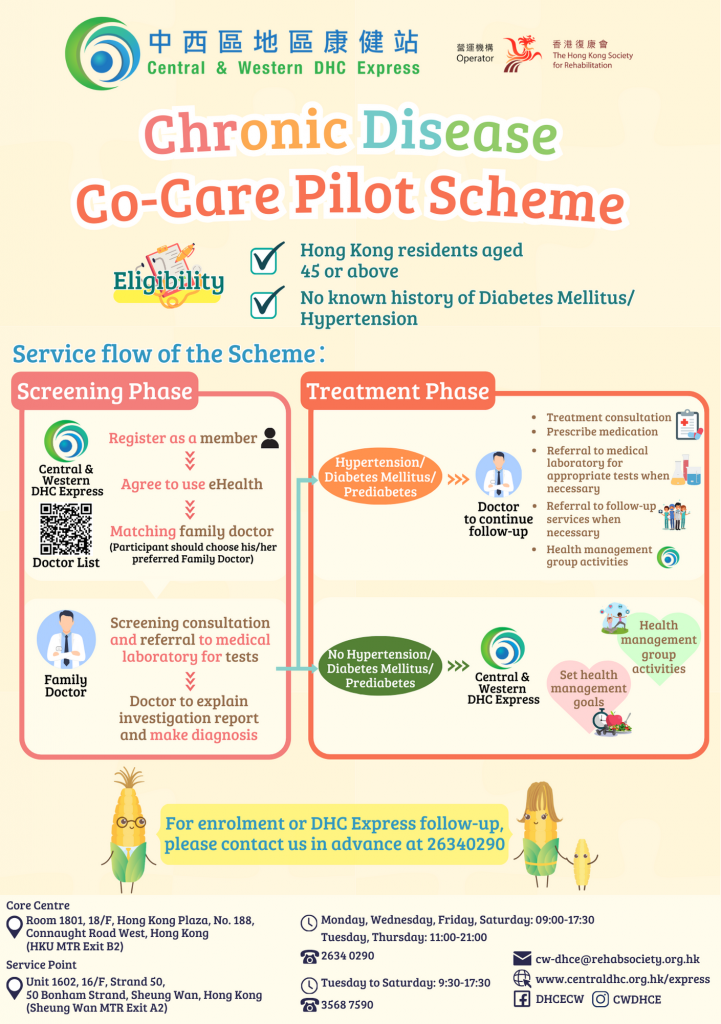

Particularly impressive are the targeted efforts to protect vulnerable populations, especially seniors. The Senior Citizen Home Safety Association (SCHSA) has pioneered innovative services that integrate real-time weather information with emergency support. Their dedicated “Weather Information for Senior Citizens” webpage and joint press conferences ensure that older residents receive timely, critical information during extreme weather events.

Public engagement has emerged as a crucial strategy in Hong Kong’s heat management approach. Organizations like the Hong Kong Red Cross actively involve volunteers in community education, distributing heat-related information and providing targeted support to at-risk groups. The HKO leverages multiple communication channels—traditional media, mobile apps, social platforms—to disseminate weather warnings and heat stress information, ensuring widespread accessibility.

Urban planning has also become a critical tool in mitigating heat risks. Hong Kong’s urban climatic map classifies the city into different thermal zones, providing recommended design actions for new town planning and urban renewal. This approach considers how building design and urban layout can significantly reduce heat island effects and improve living conditions.

Ongoing research continues to push boundaries, exploring complex relationships between heat and health. Current studies examine everything from the microclimates of urban street canyons to the potential impacts of high temperatures on allergic symptoms. Researchers are also developing the Hong Kong Heat-Health Warning System, which promises more sophisticated predictive capabilities.

The city’s collaborative approach involves multiple government departments, including the Department of Health, Labour Department, and Home Affairs Department. By working together, these agencies provide heat shelters, develop safety guidelines, and create comprehensive support networks.

For residents, the key takeaway is clear: heat is not just a meteorological phenomenon but a serious health consideration. Staying informed, understanding personal risk factors, and knowing how to access support during extreme temperatures are crucial survival skills in Hong Kong’s evolving urban environment.

As climate change continues to reshape urban experiences, Hong Kong stands as a compelling example of proactive, research-driven adaptation—demonstrating how cities can transform environmental challenges into opportunities for innovation and community resilience.