Rising Mosquito Disease Risks: More Than Just Chikungunya to Worry About

Climate change is reshaping our world in ways we’re only beginning to understand, and one of the most alarming transformations involves the spread of mosquito-borne diseases. What was once primarily a tropical health concern is now becoming a global threat, with potentially billions of people facing new risks in regions previously considered safe.

The dramatic expansion of mosquito habitats is driven by rising global temperatures and increased atmospheric moisture. Over the past two decades, Europe’s 10°C temperature line has shifted an astonishing 240 kilometers northward, allowing disease-carrying mosquitoes to survive in places they could never have imagined before. Cities like Paris, Beijing, and regions across the British Isles and southern Scandinavia are now potential breeding grounds for dangerous mosquito species.

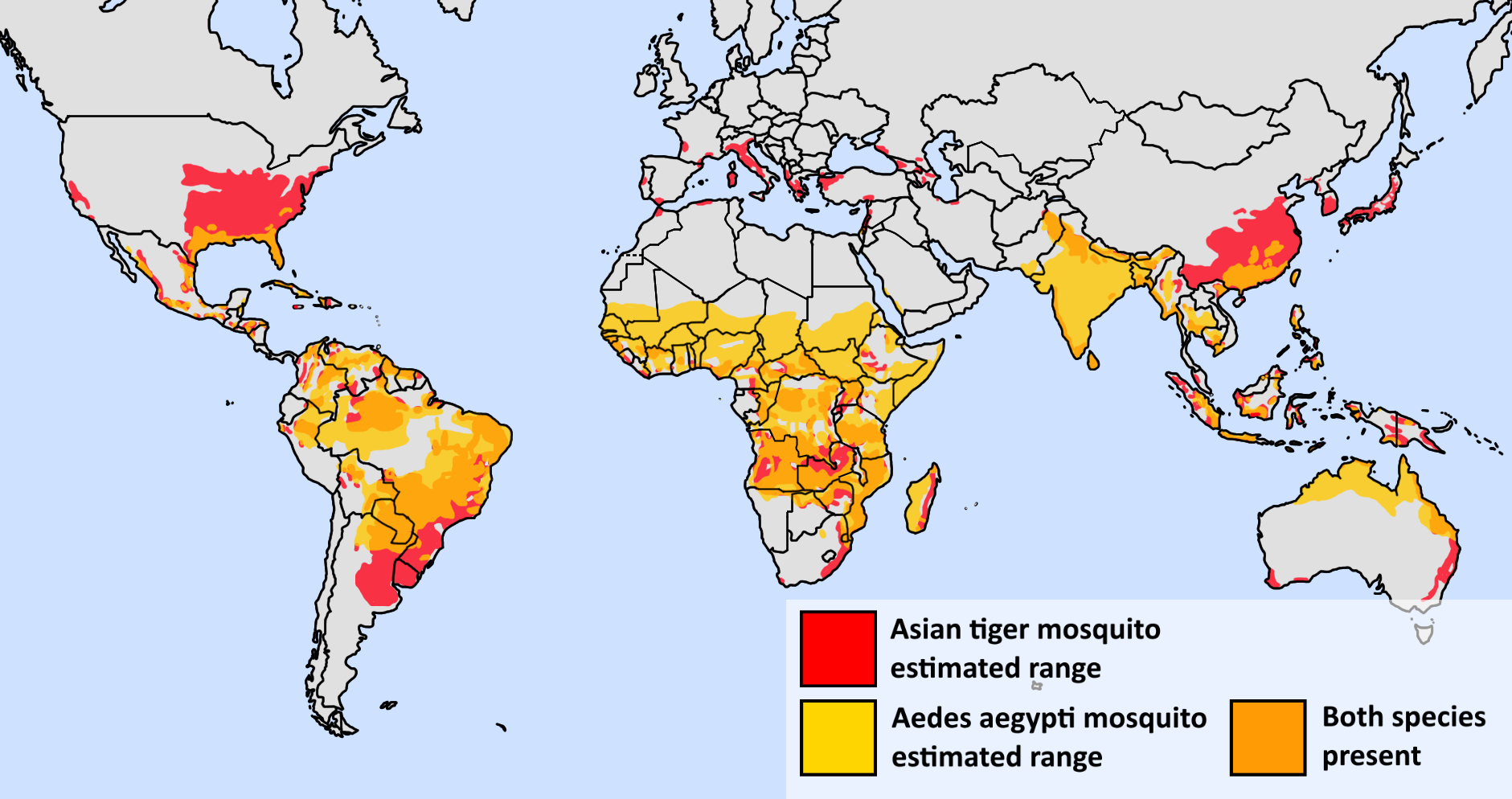

Two primary mosquito species are leading this concerning migration: the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti). These tiny but formidable insects can now thrive in environments that were once too cold, bringing with them the potential for diseases like chikungunya, dengue, Zika, and yellow fever.

The breeding patterns of these mosquitoes make them particularly challenging to control. They require minimal water to reproduce—even small puddles in dish racks or bathroom corners can serve as breeding sites. Temperature plays a crucial role in their development, with mosquito eggs maturing in as little as 5 days when temperatures reach 35°C, compared to 19 days at 20°C. This means warmer summers dramatically accelerate their reproductive cycles.

Experts project that a mere 1°C rise in global land temperatures within the next 20-30 years could expose an additional 4.7 billion people to mosquito-borne disease risks. This isn’t just a theoretical concern—local transmission of diseases like dengue has already become routine in countries such as France, Italy, and Croatia.

Personal protection is critical, but public awareness remains surprisingly low. Only one in three people in major cities know how to effectively repel mosquitoes. Scientific research recommends specific repellents for maximum protection: DEET at 30% concentration provides 5-6 hours of coverage, while Icaridin and IR3535 (at 15% concentration) offer reliable defense. Cream-based repellents tend to provide longer-lasting protection compared to sprays.

Future strategies for mosquito control include innovative approaches like gene-edited sterile mosquitoes. However, scientists caution that complete eradication could potentially force pathogens to adapt and find alternative transmission methods.

The most critical takeaway is that mosquito-borne diseases are no longer just a tropical problem. They represent a growing global health challenge that requires collective awareness, personal protection, and adaptive strategies. While individual outbreaks might not always reach catastrophic levels—some diseases like chikungunya offer lifelong immunity after infection—the cumulative impact of recurring disease waves poses significant risks.

As these health threats become more prevalent worldwide, individuals and communities must prioritize prevention, stay informed about local risks, and consider comprehensive protection strategies. Whether through personal protective measures, community awareness, or exploring health insurance options that cover emerging disease risks, proactive preparation is key to navigating this evolving landscape.

The message is clear: mosquito-borne diseases are a complex and growing challenge that demands our attention, understanding, and collective action.